History of the Macedonian Film

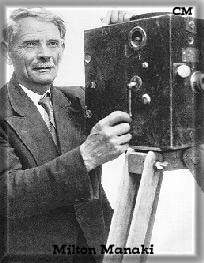

The appearance of the cinema in Macedonia dates from the beginning of the 20th century. Ten years after the promotion of this new art at the famous Grande Caffe in Paris (1895), the Manaki brothers shot the first filmed scenes in the Balkans, on Macedonian soil, thus marking the expansion of the new medium.

The shots by Milton and Janaki Manaki at the beginning of their careers were in Bitola, Bar, and Avdela. Conceived as individual film episodes, these scenes of family life and collective rites and customs have preserved their documentary and ethnologic value up to the present day (these include Despa Manaki Spinning, The Celebration of Epiphany, A Fair in Ber). However, scenes of films made in the following years already announced the maturity of Milton's talent. In the documentary about the visit of Sultan Reshad to Thessaloniki and Bitola (1911), he displayed abundant documentary material in more complex genre forms (feuilleton, chronicle, and report).of the new medium. The shots by Milton and Janaki Manaki at the beginning of their careers were in Bitola, Bar, and Avdela. Conceived as individual film episodes, these scenes of family life and collective rites and customs have preserved their documentary and ethnologic value up to the present day (these include Despa Manaki Spinning, The Celebration of Epiphany, A Fair in Ber). However, scenes of films made in the following years already announced the maturity of Milton's talent. In the documentary about the visit of Sultan Reshad to Thessaloniki and Bitola (1911), he displayed abundant documentary material in more complex genre forms (feuilleton, chronicle, and report).of the new medium.

Before the Manaki brothers appeared, there had already been a number of travelling artists, whose programs included the sensational presentations of "moving pictures."

The first projection took place as early as 1896, and by the beginning of the 20th century they grew frequent.

An increasing number of projectors were owned and operated by such individuals as Milan Golubovski from Skopje and Konstantin Comu from Bitola.

In this period, the cinema careers of the Manaki brothers did not gain many supporters and successors. It was not until the Ilinden Uprising and post-llinden events that Macedonia became an area of interest for foreign film-makers. Patte staged scenes of bloodshed in Macedonia, wishing to direct attention to the resistance of the Macedonian people. Much more valuable to the historian than these stage-managed massacres and atrocities are the authentic documentary films about the battles at Bregalnica and Skopje, made by the cameramen of Patti, Gaumont, and other Austro-Hungarian and German companies.

In the interwar period, Macedonia occasionally spawned film enthusiasts, such as Arsenie Jovakov and Georgi Zankov, authors of the documentary Macedonia (1923), and vigorous professionals such as Riste Zerdeski — actor, cameraman, producer, and creator of the feature film The Two of Them in Zagreb.

A greater degree of organisation in the programmes was introduced in the 1930s by the Skopje Public Health Institute. Their list included a considerable number of stories with didactic themes, as well as the feature film Malaria, filmed in 1932. In this period, the documentary director Blagoja Drnkov began his prolific film-making career, leaving behind a rich collection of works with high ethnological and historical value: notably, the Bombing of Bitola and The Gliders’ Meeting in Skopje, both from 1940.

In 1945, the first institution for organised production, distribution, and display of films in Macedonia, FIDIMA, was founded. This was the beginning of mobilisation of the Macedonian film industry. It has continued to the present day, although not without productive and qualitative unevenness.

A large number of Macedonian film-makers were integrated in the production house Vardar Film (established in 1947). Here, the emphasis was on making films with historical content and themes. The historical spectacle remained, for a long time, one of the preoccupations of the directors and producers; the doyen of post-war documentary film, Trajce Popov, likewise gave his contribution to the promotion of this genre (Macedonian Blood Wedding, 1967). Directors of the younger generations followed this lead, such as Ljubisa Georgievski (A Blazing Republic, 1969), Kiril Cenevski (Bitterness, 1975), and directors who had often been guests of Vardar Film, such as Zika Mitrovic (Miss Stone, 1958).

The films are often interwoven with the theme of war: Frosina, 1952 (the first Macedonian feature film), The Macedonian Share of Hell, 1971, Black Seed, 1971 (where Kiril Cenevski was discovered, winner of The Golden Arena in Pula, and acknowledgment at the International Festival in Moscow). War films like The Price of the City, 1970 made use of the motifs of ancient legends, while the drama of The Wolves' Night, 1955, recognised the spirit of moral stoicism, skepticism, and fighting asceticism.

Macedonian films demonstrated much greater creative thought, originality of ideas, and boldness of poetics in the part of production which treated issues of contemporary moral behavior. For modern dilemmas and temptations, analogies are looked for in the past: Time Without a War, 1969, by Branko Gapo, used Biblical analogies to link the fates of the father and the son in two different social environs — the war and the peacetime period. Stole Popov used the themes of the exodus of the Macedonian population (The Red Horse, 1981), the tragic period of the Cominform, when ideals were lost along with the disintegration of the homogeneous communities like that of the family (Happy New 1949, 1986, winner of The Golden Arena in Pula), and the degradation of the individual to the point of physical destruction (Tattooing, 1991).

Close to both the thematic and creative position of these films was the feature debut of Vladimir Blazevski, Hi-Fi, in 1987, followed by debuts in single episodes of the film Light-Grey, 1993, of Aleksandar Popovski, Srgjan Janicievic, and Darko Mitrevski. An outstanding success was achieved by Milco Mancevski with Before the Rain, a Macedonian, English, and American co-production, winning The Golden Lion at the Venice Festival (1994) and more than 20 other awards and acknowledgments at international festivals worldwide. This film was nominated for Oscar in 1994.

It is worth noting that Macedonian motion pictures have included a wide range of themes: comedies (Peaceful Summer, 1961, by Dimitrie Osmanli); thrillers (A Visa to the Evil, 1959); melodramas (Stand Up, Delfina, 1977, by Aleksandar Gjurcinov); social plays (Thirst, 1971, by Dimitrie Osmanli); and prison films (Tattooing, 1991, by Stole Popov). Macedonian directors and animators have achieved significant success in the production of documentaries and animated films. Recent short films include several distinguished creations, which can be easily considered as world treasures. In terms of the eternal nature of the problems treated, films like Border, 1962, by Branko Gapo, Fire, 1974 and Dae, 1979, by Stole Popov (winner of a Grand-Prix in Oberhausen and an Oscar nomination), A Cudgel, 1973, by Laki Cemcev, The Sixth Player, 1976, by Koco Nedkov, The Twelve From Papradnik, 1965, by Dimitrie Osmanli, Golgotha, 1979, by Meto Petrovski, Tulgesh, 1977, by Kole Manev, Liquidator, 1983, by Trajce Popov meet, to a considerable extent, the production paradoxes which usually follow the unimpeded development of the documentary film.

This vital current was supplemented by the movement which was promoted in the early 1970s by a group of animators who, after the expansive presentations at the Yugoslav and International film festivals, found themselves on the defence. Their response, the works created by Darko Markovic (Stop, 1976, A Hand, 1980), Petar Gligorovski (Adam. 5 to 12, 1977, Phoenix, 1976), and Boro Pejcinov (Resistance, 1978), will most likely remain as lasting guarantees of the potential abilities of Macedonian animators to find appropriate creative expression for their affinities. This dimension of creation can extend to a considerable extent to the remaining part of the feature and documentary production of the Macedonian film.

From Macedonia Yesterday and Today by Jovan Pavlovski & Misel Pavlovski (www.mian.com.mk)

Written by: Gjorgji Vasilevski

Translated by: Zaharija Pavlovska

|